I grew up, in the Marianas, hearing about this gulf. In First Voyage is great gulf between what Pigafetta sees and what Pigafetta knows. And 1/20th of the profits from those lands. But there is little humility, and one can hardly expect there to be so, not early in sixteenth century, a few decades after the Pope had divided the unchartered world between Spain and Portugal,and certainly not on this expedition, where Magellan and his partners have been promised, in a contract agreement with the Spanish monarchy, the titles of Lieutenants and Governors over the lands they discover, for themselves and their heirs, in perpetuity.

He attempts to reconstruct their world for us-what they look like, where they live, what they eat, what they say-he gives us pages and pages of words, from Patagonia, from Cebu, from Tidore. Pigafetta, encountering a new people, tries to earn his authority through a barrage of detail. For the travel writer there is, on the one hand, the authority of his or her observational eye, and on the other, the call for humility in confronting the unknown.

On a stop in Brazil, we see an infinite number of parrots, monkeys that look like lions, and "swine that have their navels on their backs, and large birds with beaks like spoons and no tongues" (10).Īnd yet, the very newness that can give travel writing so much of its power creates problems of its own. We marvel, in the Philippines, at sea snails capable of felling whales, by feeding on their hearts once ingested (48). I believe those leaves live on nothing but air.” (Pigafetta, 76). When I opened the box, that leaf went round and round it.

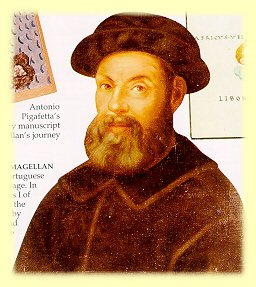

I kept one of them for nine days in a box. We watch Pigafetta wonder at trees in Borneo whose leaves appear to walk around once shed, leaves that "have no blood, but if one touches them they run away. In travel writing, one often must recreate the first moment of newness, that fresh sense of awe, on the page for the reader Pigafetta does it again and again, by reveling in odd and odder bits of detail. One of Pigafetta’s patrons, Francesco Chiericati, called the journal “a divine thing” (xl), and Shakespeare himself seems to have been inspired by work: Setebos, a deity invoked in Pigafetta’s text by men of Patagonia, makes an appearance in The Tempest (x-xi).įirst Voyage, Cachey points out, is intent on marveling at what it encounters-and therein lies much of its appeal. According to scholar Theodore Cachey Jr., the travelogue represented “the literary epitome of its genre” and achieved an international reputation (Cachey, xii-xiii). Pigafetta’s journal became the basis for his 1525 travelogue, The First Voyage Around the World. And along the way, new land, new peoples: on the far side of the Pacific, the fleet had stumbled across the Marianas archipelago, and some three hundred leagues further west, the Philippines. Pigafetta had managed to survive, along with his journal-notes that detailed the discovery of the western route to the Moluccas. Of the 237 sailors who departed from Seville, eighteen returned on the Victoria. The rest of the fleet was gone: the Santiago shipwrecked, the San Antonio overtaken, the Concepcion burned and the Trinidad abandoned. On board was Antonio Pigafetta, a young Italian nobleman who had joined the expedition three years before, and served as an assistant to Ferdinand Magellan en route to the Molucca Islands. On September 8, 1522, the crew of the Victoria cast anchor in the waters off of Seville, Spain, having just completed the first circumnavigation of the world.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)